Seeing through an artist’s eyes

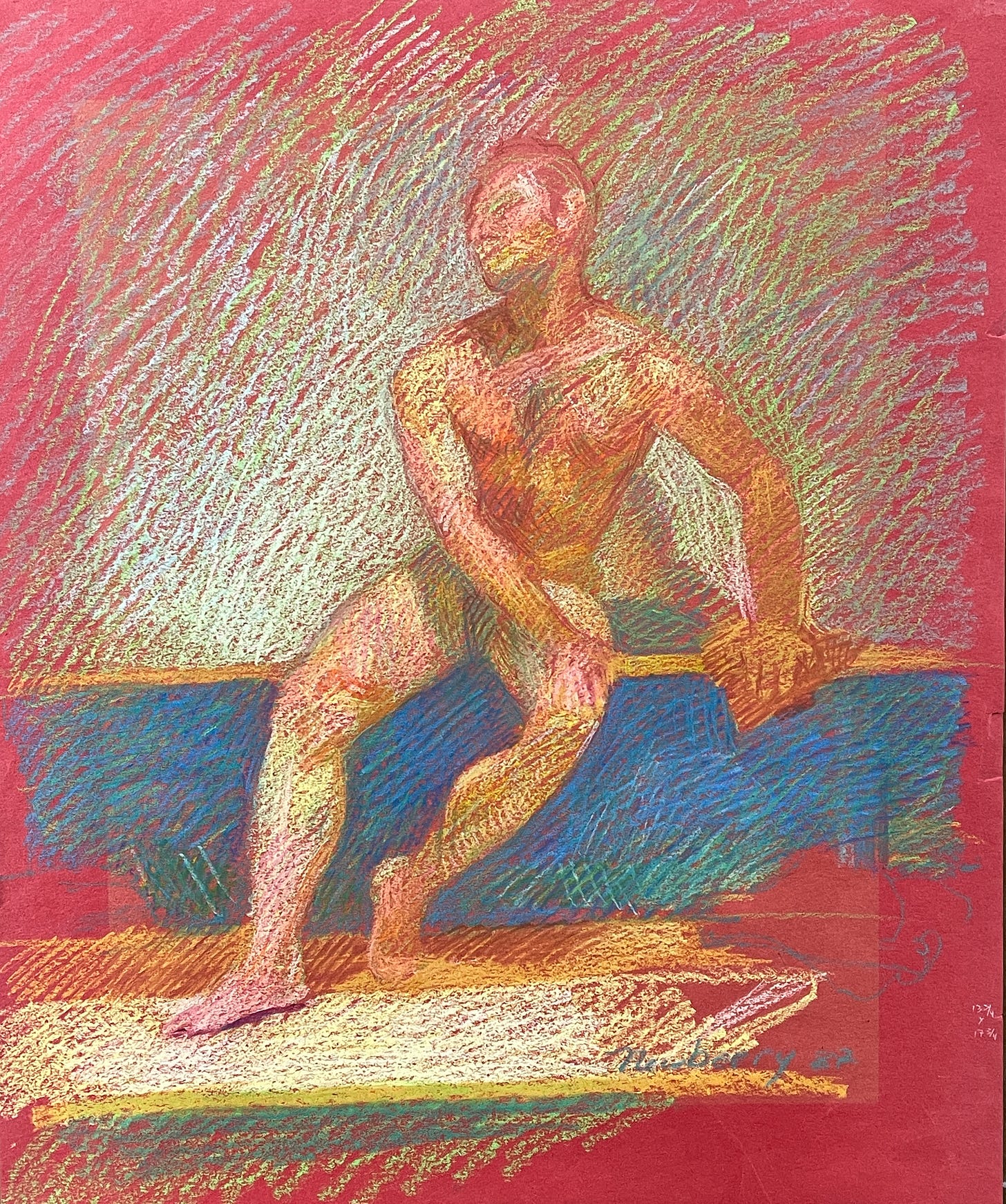

Another work that recently came back into my possession is this life drawing on red paper (1987), I was 30, and it was the same year I completed one of my most important works, Denouement (image lower in the post).

I didn’t so much have a color theory as I had an observational approach. Later I developed the Newberry Color Theory, but that came after decades of observing perceptual effects of color and how they work as artist tools in creating form, light, and space. For me as an artist, color was never anything in and of itself. For example, simple colors don’t have any meaning to me whatsoever, like the color blue. My interest in color is how it works with form, light, and space.

If I unpack the drawing on the red paper, it’s a fascinating problem because, actually, instead of making up any of the colors, I was drawing the color vibrations that I saw, going from the general to the specific with more time. The figure drawing was a three hour life drawing session. But as soon as you put a color on the red paper, something dynamic happens.

For example, you could take a magenta pastel and put it on the red paper, and it will register cool. Because the magenta mixes with the blue, the red and blue on the red paper, the bluish tint is what surfaces. When on another colored paper, like green or blue, the magenta pastel color will register as extremely hot.

If you squint looking at the same magenta color you may be able to sense the coolness of it above, and hotness of it below.

My process was not to pick a color of what I thought the thing was when I was looking, but to find the pastel color that, on the red paper, would register the right kind of light frequency or color frequency. If I was seeing a flesh color, if I used that flesh color on the red paper, it would look sickly gray. Whereas orange or scarlet might register as a flesh color.

For every single color I was making, I had to try it out to see what would happen on the red paper and then, consequently, what would happen on the layers of the other colors. Every single mark was judged not on what color I thought the image needed as a next step, but with my viewing of the setting, to get closer to the color vibration that I was seeing, whether it was cool, warm, or yellowish.

One incredible device that is extremely important is squinting your eyes. Squinting your eyes gets rid of all the details, but what’s left are the tonal and hue effects of light and shadow. With your eyes completely open, it’s hard to sort through all the sensory info. It’s way too much information, all these minute bits of information. While, the squinting gives you the big picture of what the light is doing.

In my pastels, what I aim for is simply to get a true image of what the light color is doing.

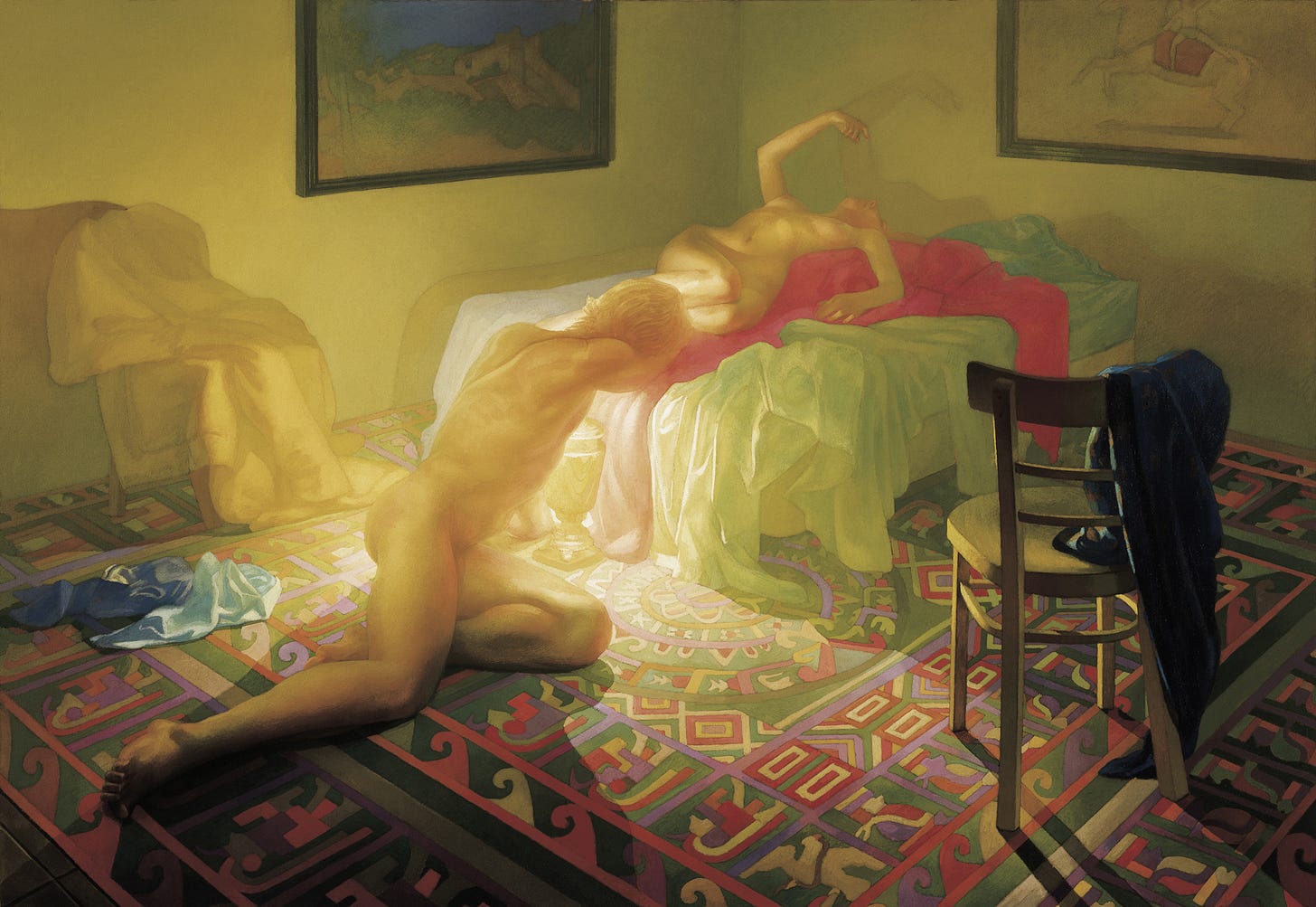

The painting Denouement was a three year project of working Monday through Friday, around the clock. I had a part time job on the weekends teaching tennis at the famous Jack Kramer Club and giving playing lessons to the great tennis player young Pete Sampras. The club even offered me the Head Pro position, but that would have killed my art career. So I opted to stay on two days a week.

With the painting Denouement, I made hundreds of pastel studies of the scene and the background. I would have models come and pose, and I would use my squinting technique to discern the colors in my pastel studies on colored paper. I remember several attempts looking for the right key of the reality in the right colored paper that would give the painting this particular glow.

At the time, I knew the rudiments of color theory, of classical color theory. Like in a landscape painting, traditionally cool colors recede and warm colors come forward. But that wasn’t the way that I learned art. I learned art primarily from my own observation of things.

I would compare and contrast the light color vibrations of one area, let’s say a background corner, with a foreground corner, and try to capture the difference of the color tints. I had a very exact, and I still do, scientific method of observation, of really discerning in a very, very careful and nuanced way the color vibrations that I really see in life.

There is a cognitive value to this process, emotionally, intellectually, and perceptually. Emotionally, it gives us a tremendous sense of relief, empowerment, and awareness of being in the moment. Intellectually, it gives an important foundation of perceptual awareness of the real world. Perceptually, it solidly enhances and refines our powers of observation.

The exhilaration of seeing color vibrations flowing is one of the most exalted experiences I know.

Wow! Your artwork is mesmerizing. Beautiful work.

A lovely read and very insightful!

Thank you so much, Lina!